RoboCop

The original RoboCop by Paul Verhoeven and Edward Neumeier is a great film. It is about a robot police officer, but it's also about a city ruined by privatization and corporate malfeasance. The police officer - an object both human and a public resource - is literally ripped apart and put back together as neither. His new form is optimized for capital and private military-industrial ends. It succeeds as action, body horror, dark comedy, and allegory.

The new version is awful. To begin, RoboCop somehow suffers fourth-degree burns everywhere but his ruggedly handsome face. The original RoboCop was disquieting even in full gear and hideous without. This is RoboCop, Designed in Cupertino and Assembled in China.1 Usually he just looks like a guy in a suit; even disassembled his viscera remain safe (not from medical complications, but from us having to confront them) behind spotless Gorilla Glass. The closest it gets to frightening is a subplot about free will and determinism which is completely ignored during the second half - maybe for the better, because it's introduced in a way that could only lead to pop cogsci retreads of "what is free will anyway?"

Beyond the visual design, though - the original was a story of systems, specifically capital forcing its way into civic law enforcement. RoboCop was the narrative focus, but he wasn't a character so much as the battleground. In the new film, RoboCop is brought back with his humanity fully intact, only to have it stripped, then magically regained. The focus is on him as a (frankly boring) person. It's framed like a story of a disabled person overcoming adversity, except even his "disability" only lasts for a short time, and he's still super-strong and super-fast. If you want a film where a superhero grapples with mundane personal demons his superpowers cannot solve, Iron Man 3 covers much more ground.

The personal focus loses the transhumanist aspect as well. At the end of the original film it's difficult describing RoboCop as human, as it is saying he's an unfeeling machine. That RoboCop recovers autonomy and purpose, but never humanity. The new one is a human with expensive prostheses.

And whatever this film is trying to say about militarism, colonialism, or law enforcement, it says too little, or too late, or both. America already uses drones to terrorize civilians - that they're not human-shaped doesn't matter or is even an "advantage" - and civilian law enforcement is already buying them for domestic use. A speculative dystopian future could stand as its own commentary, but a slightly-tweaked view of our current policy needs some push-back to be considered critical rather than dangerously complacent.

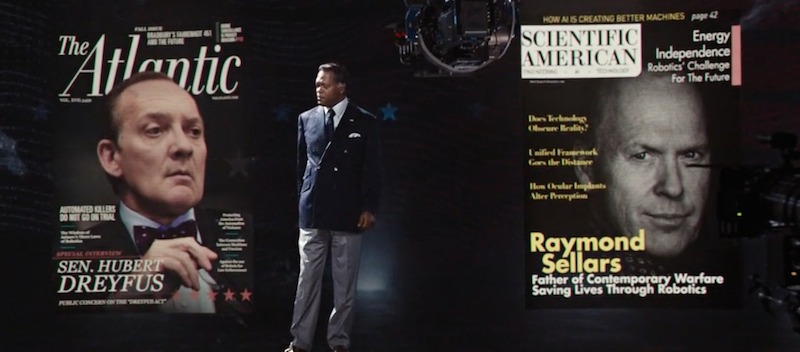

The short version is, here's the smartest scene in it. It lasts a few seconds and it's the only thing in a nearly two hour film that has the zing of the original - "he said, she said" journalism; the subtle complacency of popular science and scientism in supporting American neo-conservatism; the fact our civic choices are often between an ineffectual and ironic centralized populism versus a rich man who might let us borrow his toys.

-

Literally, he wakes up in a Foxconn-esque factory. ↩